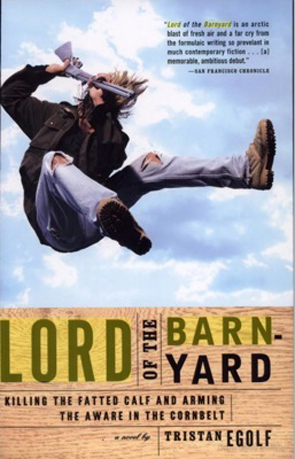

Lord of the Barnyard was a novel first, printed in 17 languages and greeted to rave reviews. It was written by a young author named Tristan Egolf, who I befriended after Sundance when I optioned the book. Sadly, he put a shotgun in his mouth and killed himself a few years later. The screenplay, which he approved, is the story of a lowly bunch of garbage collectors who decide one day that they will simply stop picking up the trash. With nobody else to do the job, the town of Baker, Indiana makes a series of ill-considered judgments, resulting in a debacle of near-Biblical proportions.

I know film people often criticize the use of voice-over. I choose it for this film because the story is told in the manner of a tall tale, and a narrator needs to play an important role as Storyteller. He is also a character, Wilbur Altemeyer, who works at the town landfill, who knew John Kaltenbrunner, and was his only lifelong friend. Wilbur is a disciple, recounting the story of the infamous John Kaltenbrunner, as one of the people whose life John touched. The community he leaves behind is divided about John; some think of him as a great man, while others consider him a swindler, a blackmailer, and a provocateur.

The film begins when John is a small boy, and he first exhibits great genius as well as a capacity for violence. It begins with the death of his father, and the physical and emotional deterioration of his mother, when John is 13. Left to himself for long periods, he applies himself to the family farm with a manic energy, transforming it into a thing of wonder: child-like in its creativity, efficient for the tasks needed. He finds a way back to his father by uncovering a vault of his belongings. He is as close to happiness as he has ever been.

Some local Methodists begin to work on John’s mother as her health deteriorates. They would like to take over her estate and see to her needs and John’s needs. They force John to return to school. His mother signs away the farm while he is at school one day. As she nears death, and John faces the prospect of losing his beloved farm, he resolves not to let them have it. He wires the place with explosives, wheels his mother out into the front yard, and blows the place to bits. He is taken away by the state police.

The film jumps twenty years, to when John is 33. Nobody recognizes him in Baker now. Down on his luck, sick, dirt poor, he is barely scraping by when Wilbur befriends him. Wilbur and John develop an uneasy friendship, between a gentle and nurturing man and a wounded animal. And Wilbur finds a job for John at the dump.

As John’s health improves, he begins to regain his spirit. As he looks around at the dump, he sees a lot of room for improvement. The operation itself is inefficient. And the way that the people of Baker treat the collectors abuses John’s sense of dignity. And the workers themselves don’t do a very good job. He begins to question why it has to be this way. And that’s when the trouble starts.

One day, he defends a co-worker from an angry citizen, and stands up to an abusive foreman. He develops a new route structure behind the foreman’s back, and pretty soon the place runs smoother. Then one day, after the abuse of one employee becomes too much to bear, he announces his plan for a general strike. They will simply stop showing up. They will post a notice demanding changes, and Baker will have to capitulate. Or they will drown in their own garbage.

Baker doesn’t see it John’s way. First, people don’t notice. Then they don’t want to capitulate. The Sheriff and the Mayor face off against each other. And as the garbage mounts, the town becomes angrier and angrier. The media arrive. The Mayor discovers who is behind the strike, and John becomes the enemy of all of Baker. The town does eventually does capitulate, and the garbage men of Baker gain new-found dignity. But John must leave, and he vanishes one night, leaving only his memory, and a legend that grows with the telling.